Let’s imagine a new world

- Amit is opening an account with Monyz, the trendy neobank. He downloads the app, opens IDNow – a mobile wallet with his identity and credentials – and authenticates himself using faceID. He shares credentials through IDNow with Monyz to get set up. He gives Monyz access to his name, confirmation that he resides in Canada and that he’s above 18. He doesn’t share his exact address or date of birth to protect his privacy. The app auto-populates the necessary data using the credentials he has shared. Within minutes, he’s ready to use Monyz. The neobank offers him an unsecured loan at 5% per year if he shares his credit history. Amit could certainly use the money. He shares access to his credit history with them through IDNow. The Monyz algorithm reads the credit history, crunches the data and a minute later, Amit has a $10,000 loan available to him.

- Ashley is visiting New Zealand and wants to go on a road trip in the beautiful country. She books a rental car on Rentacar’s website and pays the booking amount using IDLive. Rentacar asks for confirmation that she has a driving license valid for New Zealand. She confirms this through IDLive without sharing the details of her driving license. A virtual car key is sent to her IDLive wallet. On the day of the road trip, she goes to the Rentacar parking lot and taps her phone on the NFC receiver on the car. The car verifies her identity and that her driving license has not been revoked since she made the booking. The car door unlocks and she drive away.

- Obi just completed his undergraduate degree in computer science from the University of Lagos in Nigeria. His dream is to go to the US for a masters degree, just like his father did. He applies online for the master’s program at Stanford. Stanford needs to confirm his educational credentials. Obi connects to his EagleID wallet on his computer which stores his ID and credentials and authorizes Stanford to see the details of his degree and computer science course credits. Verification completed in an instant, he starts focusing on writing a great essay and preparing for the interview. Competition will be tough. Thankfully, he doesn’t need to spend six months running around to get a letter from his university and wait for Stanford to validate it, like his father once had to.

You may say, I’m a dreamer. But I’m not the only one. Several organizations are working on creating seamless global identity and credential systems using the innovation called digital decentralized IDs (DIDs).

But first, let’s back up a little bit.

Today’s IDs are not IDeal

IDs and credentials are a prerequisite for accessing many online and offline services. We rely on the credentials on our driving license every time we drive. We rely on our provincial health card for public health services. We rely on a valid proof of residency – a passport, permanent residence card or visa – to live in a country. We use our ID to log into any service online. A credit card is a payment method linked to our identity. We probably don’t notice how much we rely on them daily because they’re so pervasive.

However, most of our IDs today are not portable. Our identity and credential data is issued by siloed institutions and stored centrally in their digital or physical databases. You university degree details, for example, are stored in an electronic database controlled by your university. In parts of the world, this data still sits in physical books. These databases are not open to the public so the only way to truly verify that the credentials you’re presenting to a third party are genuine is to go back to these institutions and ask. This process can be slow, cumbersome and expensive. In some cases, it might fail – for example, if the university shuts down. So either verifiers conduct ‘pseudo-verification’ (“I think your degree is genuine”) or you spend days, weeks or months getting them validated from the relevant institution.

The other issue is that our IDs and credential documents are designed for physical formats. My passport, driving license, health card and university degrees are all physical documents. This means that, i) sharing this information with others requires digital photos or photocopies that need to be manually verified, and ii) I cannot selectively share relevant information about a credential with anyone that requires it – it’s all or nothing.

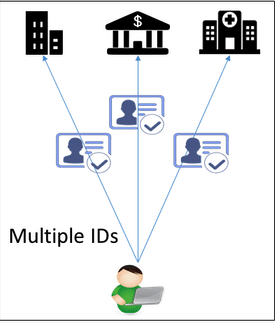

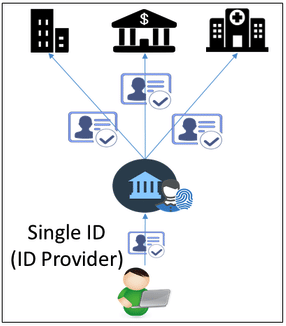

On the internet, similarly, websites ask you to create a login and password that is centrally stored on their databases (hopefully in encrypted form). If they collect any additional data on you – for example, photos of physical IDs – that is also maintained on their own databases. Their databases are also closed to outsiders, which means that every time you want to create an account on another website, you need to go through the same process all over again. Websites are prone to hacks, and given that the most common login ID is your email, you need to maintain a roster of different passwords so that hackers can’t use stolen credentials from one website to access your account on others. The other challenge with your email as login ID is that websites have a unique identifier to buy or trade information about you with others and know more about you than you want them to. You really can’t control what happens with your information once you’ve given it to them.

Large players like Google and Facebook came up with a partial solution to this multiple ID creation issue – ID as a service. Now, you can log on to various websites (that have integrated the service from Google or Facebook) securely using one of these accounts. The website doesn’t get your login credentials, just verification that it is you and certain data points that they request from the ID service. This is called the federated model – using one secure login service for accessing multiple services. This is certainly an upgrade from the previous model. Despite what the media says, I do trust Google to keep my data more secure than that website that launched three days ago.

Another successful implementation of a federated or semi-centralized model is the digital ID issued by Sweden, called BankID. Residents can obtain a BankID through their banks who have already conducted KYC on them, and use them for a variety of things, including access to government institutions, health facilities, pharmacies, educations institutions and even to digitally sign contracts. Given banks are heavily regulated, conduct extensive KYC and have highly secure systems, they are an ideal choice for providing a portable ID service. Nearly 80% of Swedish residents have a BankID, a testament to the success of a voluntary program. SecureKey in Canada also allows you to use your bank login to access government and a host of other services.

However, there are still challenges in this model:

- The point of failure is more centralized now. What if Google’s or the banks’ services go down, they get hacked or go bust?

- Linked to the centralization point above, my ID could be revoked for reasons beyond my control and lock me out from critical services

- These service providers now know a lot more about me than I want them to, namely which other websites and services I use and how often

So, what if there was a way to:

- have various institution issue my credentials digitally which are then stored somewhere securely, irrespective of what happens to the institution,

- own full access to the credential and authorize others, at my command, to view only the parts of the identification or credential information I want to share with them, and

- give the verifier means to verify the information digitally without having to rely on the institution that issued it?

DID you say there’s a better way?

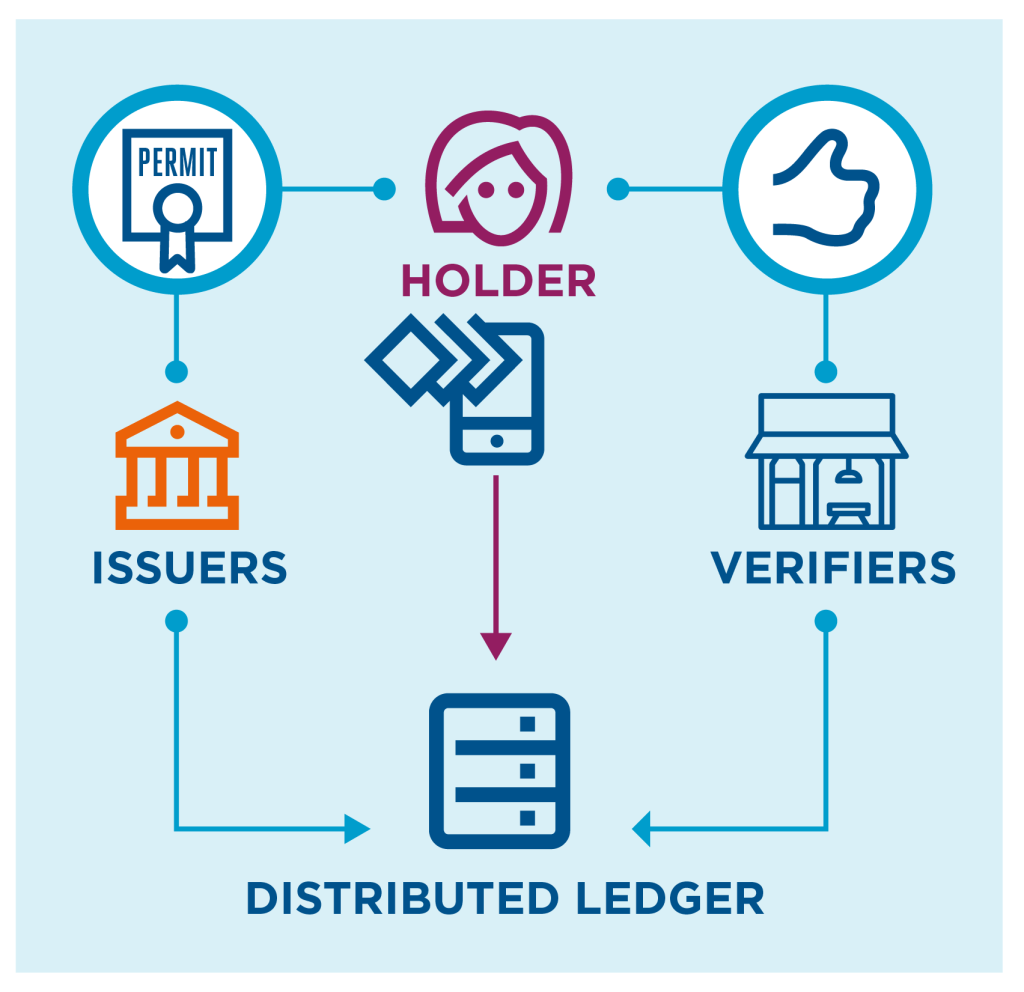

That is the promise that decentralized IDs (DIDs) hold.

A DID is a digital ID that you maintain on a digital wallet on your own device and issue to a requestor. This digital ID is linked to credentials (called DID documents) issued to you by third parties (such as governments and universities) that are stored securely in encrypted form on decentralized storage systems such as a distributed ledgers or blockchains. Maintaining DID documents on a distributed system helps ensure that the security and availability of the data is not reliant on any one institution. You give access to the verifier to your DID document and they check it on the decentralized storage system.

We won’t dive into the technical details, but linked to the DID document is a public reference (called a public key) that can be shared and a private reference (the private key) that only you know. The DID document can be decoded and accessed only when the public key is matched with the private key, so you control who can see the information even though it sits on a distributed system.

Since DID documents are digital, you don’t need to give access to the entire document. You can share only relevant information from a document, combine information from multiple documents, and answer questions like, “Are you over 18?” rather than sharing your date of birth. The other exciting thing is that you can reduce the ability of websites to track or trade your information across other online services. You can create a new DID for every service you use so that they don’t have a unique identifier for you (such as your email).

So this seems great. But how do we build this?

I DIDn’t say it would be easy

DIDs are still very early and there’s a long road ahead to make them ubiquitous. But a lot of promising work is being done and organizations are forging ahead to make them a reality. Here’s an overview of what we need to achieve.

The first step is to define common standards that issuers, users and requestors can agree and build upon so that these IDs are truly universal. There are several organizations that are working on defining standards for various parts of the stack: W3C, DIF, IETF, among others. I’m not aware if there is consensus on the standards yet, or if various standards will be set up for interoperability.

Next is to build the infrastructure that issuers, people and verifiers will use. The EU has started work on this with the ESSIF digital identity initiative. Canada is working on this through DIACC and the VON initiative.

Then we need to get issuers to adopt this new way of issuing credentials. I think getting every (or even most) institution to invest money, people and training into adopting this is going to be the longest and toughest part of the process. Bootstrapping the network successfully is essential here. Without widespread adoption from credential issuers, DIDs will have limited applicability and, thus, low user adoption. A consultative process with a government-mandated push could be the answer here.

The next step is to get credential requesters to adopt this. I see two types of credential requesters: i) government departments and government-funded institutions, and ii) commercial enterprises. Government departments and government-funded institutions might present the same challenges as credential issuers.

However, for consumer-focused commercial enterprises, I feel this should be lesser of a challenge. Conducting KYC and managing fraud and AML, for example, is considered a necessary evil rather than a competitive advantage. If they are provided a more efficient, faster and secure way to manage this process that also reduces friction for the customer, I think they will jump on the opportunity. There might be some regulatory changes required to allow them to rely on these new methods. Challenge might come from platforms whose entire business model is linked to monetizing user data. However, given the prevailing consumer sentiment around data privacy, I don’t see them not adopting DIDs.

The economics of this new system will also have to be figured out. How would the setup and maintenance of these services be funded? How do the costs of running the distributed ledger get allocated? On the face of it, the overall amounts spent on verification (in the order of billions of dollars per year) is large enough that credential requesters would be willing to pay a fee per request for the service, that can not just cover costs but generate ROI for these institutions.

DIDs are by no means inevitable today. There are still several open questions and considerations. Countries and organizations will have different priorities and motivations. Unexpected challenges are to be expected. But this version of the future is so exciting to me that I hope we all work towards making it a reality!

Interesting. There’s merit in storing educational credentials in a digital ID. This way one can study in any country and get course exemptions instantly without waiting for months. I even like the renting a car in another country. I suspect Tesla will be the first to get on this idea.

Canadian banks will be slow to adopt. If they do, there be a thinning out of their AML departments